This post is also available via Pinecast, here, as well as Spotify.

Memories of a former world.

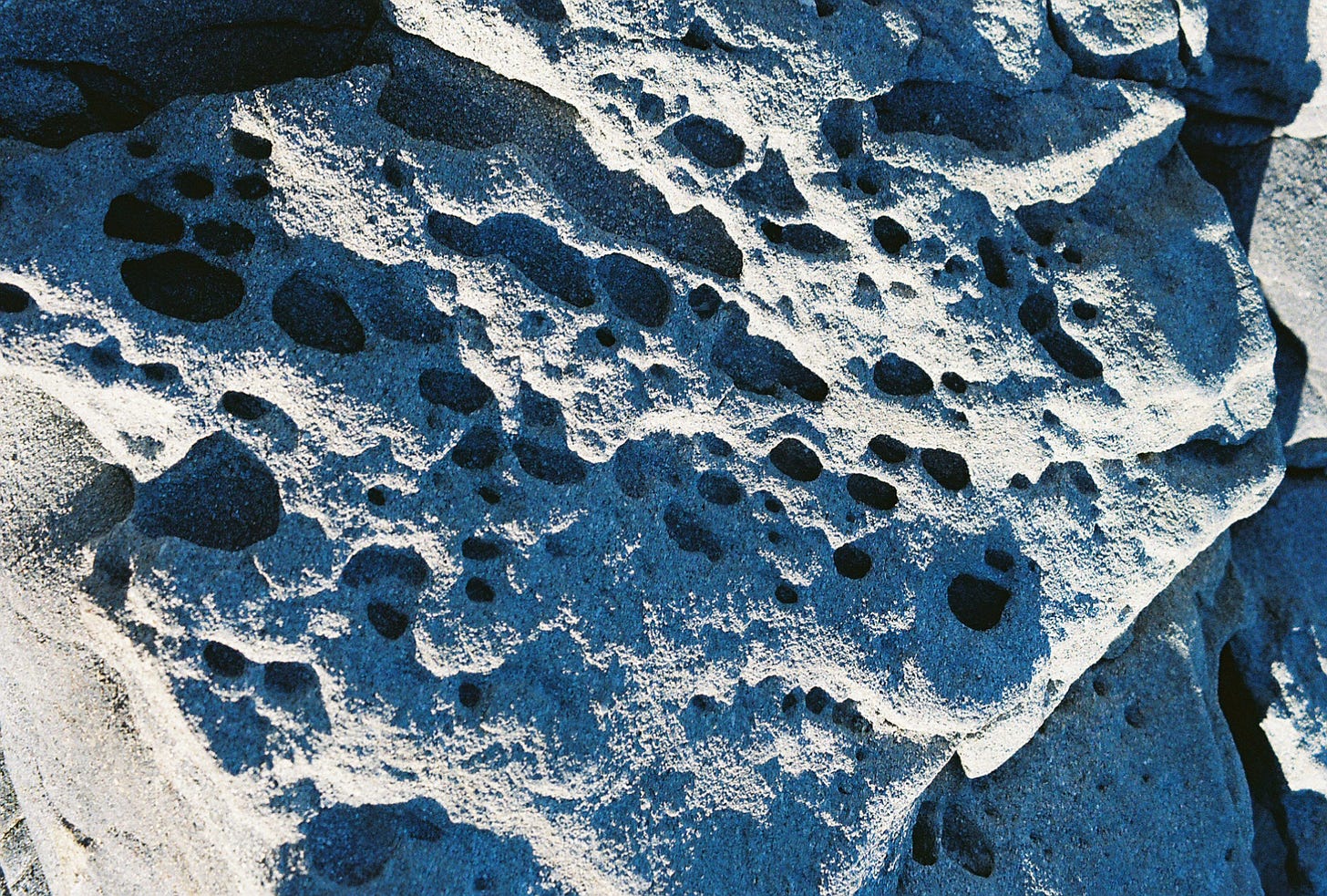

Skeletons of structures: Foundations. Steps. The metal supports of the Skyline. An olympic swimming pool filled in with concrete. The midway, or what’s left. An old parking lot. Things run through with overgrowth, before the spring cleaning of the parks department comes and trims it back again only for nature to run wild again. In the spring and early summer, you can see the invasive ornamentals, pretty pinkish-white flowers, vining, choking juniper and other native plants. Along the unpaved path, up a craigier shoreline, you can almost pretend for a moment that you’re away from people until you see the graffiti, memorials profoundly misunderstanding what it means to belong to a place or how to memorialize appropriately. Continue on. Look at the way the trees reach out. Look at the barnacles and periwinkles in tidepools, doing what they have done for years. The old asphalt road gives way to what’s below, like the other former drives allowed to disintegrate across the country, not so much unmaintained but no longer needed. We don’t drive cars here. We don’t need flat surfaces for our rollerskates and blades, our bikes, our skateboards. The rocks show the porousness of creation, craters like they came from another world. On a small shore, away from the rocks, jellyfish wash up when the weather warms, pancake discs. How many times have there been dead seagulls, memorialized here with rock circles, a grave? Don’t touch the dead. Walk into the reeds, the tall grass. Emerge back onto the paved path. Walk circles yourself to see where the world ends, becomes neighborhood, circles back to parking lot and a wide, green, hill, even green in winter. The sky, a perfect blue, betrayal, almost convincing enough to trick you into thinking it’s summer again, that you’re a child again, that the world is not so cold, that there is still amusement left, that there’s still fun to be had. I want to go back. I want to watch the water shift, knowing its tempermentality, I want the threat of it, calm now, ready to rear back and destroy if the winds pick up too high. I want to watch it dash against the rocks. I want to sit and see the dandelions which come to cover the field over the former pool, I want to look at the white lines of birch trees on the border, their own palisade. I want to pretend that other people haven’t left huge amounts of litter and trash, I want to pretend that this is a place only I’ve known about, I want to pretend that it’s something that it never was. I want to ask, why doesn’t anybody clean it up? I want to ask, if it matters so much to people, why do we not treat it like it does? I want to ask, do we just neglect everything we care about, and then always need to raise arms when it gets officially dumped the way we unofficially dumped it? Looking at the water, it’s easier. Going inside is too painful.

The Trip

I didn’t plan on going to Rocky Point State Park first. One of the driving factors behind this project has been to give me a reason to go out to all of the state parks that I haven’t been to yet, and, as it so happens, Rocky Point is a place I have been—a lot. I’ve even written about it before for my original Substack newsletter, so I’m not really treading brand new ground here. Maybe that’s okay. On January 4th, I made my first state park visit of the year and of this project. It was around 30 degrees out, with a windchill making the real feel closer to 17. But I lucked out: it was sunny.

Going outside in the winter in New England is something that is doable when you have the right clothing, like anywhere else. Below freezing is the norm for winter here, and while I don’t really love being cold, there is some comfort when the weather at least feels a little like it used to feel when I was younger—like maybe the changing climate hasn’t been so drastically altered that it’s unrecoverable, or something. The biggest differences have been in that there’s less snow here than there used to be, and sometimes snow makes the cold somewhat more tolerable, but to be honest, I’m happy enough to not have to clear my car off, and cold air feels clean to me. With me on the trip to Rocky Point this time was my coworker from the haunted house where I work seasonally, TWWWBLY podcast host and great friend, Bil Withonel. We both layered up for the trip, but I learned pretty quickly after getting to the park that I need to go to Ocean State to get some new winter gloves, and my nose immediately froze solid between the windchill factor and the fact that Rocky Point being on the water automatically makes it colder than if it weren’t. To be fair, I could have waited to start this project when it’s warm out, but also, what’s the fun in that? New England is cold for a solid four months out of the year (and sometimes longer if we’re unlucky)---if I waited, I wouldn’t be going anywhere until May. Besides that, I know people who hike in New Hampshire and Vermont in the winter, which is arguably way worse—though maybe not, since you’re working up more body heat when you’re hiking than when you’re wandering slowly around a relatively flat park? Whatever. We, bundled up, made it to the park.

It’s probably lucky that it was sunny, all things considered, because the wind was absolutely brutal. This is the truth about being on the water; it’s always going to feel about twenty degrees colder than it actually is. The wind makes the water choppy and we watch it shifting back and forth, not threateningly, but active. It’s not water I want to be in. The waterfowl have no problem with it. My Canon’s shutter keeps jamming up and I’m shooting first on expired film. The sun’s too bright and in the wrong spot for the Instax photos to come out looking anything other than overexposed, and I’m getting frustrated with how muddy the composition of the photos on my phone look. It’s simultaneously too bright to be interesting, too dead to show the things that I find most interesting about the park in the spring and summer, and, somehow, not rocky enough to show off the rocky points of Rocky Point. At least, I’m thinking this. Bil points out things to take pictures of, like the record of time in some of the rocks on the shoreline, and it helps having someone who can draw attention to things in a new way when I’m feeling like I’ve seen all these things a hundred times before. “Oh, take a picture of that,” he says, and I do, and the shutter miraculously doesn’t jam, and I finish the expired roll, which has some other photos on it, and swap it out for a new one. For the record, the reviews on Amazon are absolutely right: the new film is not as good as the Superia, even the expired Superia, that Fujifilm used to put out—but it’s fine. It works. It’s what I’m shooting on. I find that I get more enjoyment, ironically, from close up details of barnacles and the layers of shale than I do from the wider landscape shots, like the zooming in makes me pay attention in a way that makes more sense, and like the zooming in just looks better, anyway. It feels more novel that way. Reinventing the world in a different image. When I look at the periwinkles, I’m reminded of a coworker telling me how his daughter was bringing them home without realizing there were live animals inside of them. We do these things not knowing what we’re doing when we’re kids.

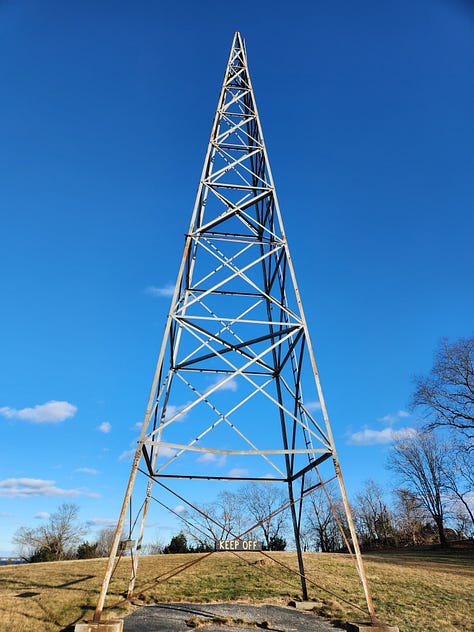

I get disheartened by the amount of graffiti on the rocks. There’s more here than there was during the summer. Someone memorializes one of their friends. I have mixed feelings. I get wanting to mourn. I don’t know these people. I don’t want to judge them, specifically. But spraypainting like this, in natural spaces, feels a lot like you’re saying explicitly, my enjoyment of this place is the only enjoyment that matters. Is that the way to mourn? I don’t know. There’s other graffiti too, including some slurs, which is like? Come on, you don’t have to do that. There’s also the remains of an old tower that’s covered in graffiti, but I feel less bothered, maybe, or more accepting, of vandalism on these ruins than the spray paint on the rocks. Maybe. Time and place. The mixed feelings come from a place of wanting to have sympathy for people, or understanding, and also irritation and frustration. I feel old saying this, but I’m over 30 now, so maybe I can say: this is vandalism. Knock it off. It’s not something that can just be painted over. These rocks have existed longer than us. Do you think that you’re so important? Even the nicer graffiti, the ones saying “Have fun,” I’m not sure how to feel about—it’s all linked together. I don’t know that it’s possible to separate out the positive graffiti from the obliviously self-centered graffiti from the outright offensive. As usual, there are other markers of humanity: trash. A ton. Litter that will outlive us. Can we do a little better?

We keep walking. I have a smaller frame, so I’m doing a little more work to get from rock to rock and not break myself or my cameras by falling than Bil is. We make our way along the rocky outcropping and back into woods, momentarily, to keep working towards the other side of the inlet. Admittedly, I really haven’t spent any time on the side of the park that actually feels like a beach. This side, that you have to go through the woods to get to, is reedier, marshier. I’ve seen a dead seagull memorialized here with a circle of shells and rocks. This is the side too that jellyfish sometimes wash up on and then cook like semi-translucent pancakes in the sun, and I always end up walking with the fear that I might step on one. I don’t know what would happen if I did, other than that it would probably be pretty gross—but I’ve never taken my shoes off here because I don’t think that the beach or the water is all that clean, and I don’t want to become the toxic avenger by getting exposed to any of it. We’re walking, and Bil shares some stories about people and places. The winter sun is getting its hazy, “It’s almost two o’clock and I want to go to bed” look about it, so we’re in an early January golden hour, and it’s only some consolation that the days are getting incrementally longer when it still feels like there is so, so little daylight available.

When I lead Bil to some tall grass—taller than me—he asks something along the lines of, “Do you know where you’re going?” And I do, but I’ve only been able to go through this path a couple of times. It’s usually too muddy. Even now, when the ground should be frozen solid because of the cold, our feet are still sticking. We emerge to the paved path walkway of the park again that we had sidestepped while walking along the rocks and through the wooded trail. Some concrete steps from when Rocky Point was still an amusement park remain, just like the asphalt which cuts into the wooded trail at the divergence point between pavement and nature. You kind of have to be looking for it, though, to know what it is. You kind of have to know what you’re looking for if you’re looking for anything here. I can imagine, for a second, if I were a child and what kind of adventure it would feel like if I were to be exploring with no concept of what had been here before, and to uncover these things with the fresh eyes of discovery.

History Of…

If I’m talking about state parks in New England, Rocky Point is a good place to start, even if it wasn’t my original intention.

Rocky Point State Park exists on the site of the former Rocky Point Amusement Park; gates, signage, and structures from the old park are still there, as is the Arch from the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens, NY. The Rocky Point Foundation, in describing the history of Rocky Point from its first use in 1847, calls it “Rhode Island’s working-class shoreline resort,” as at this point in American history and culture, working class families now had the ability to be consumers and vacationers. The new availability of leisure time in America can be seen in the development of resorts and parks across the U.S. from the mid to late 19th century and on; it is probably fair to argue that Southern New England’s relatively early development of leisure activities and resorts is a direct result of the early industrialization of the area, as the growth of both industrialism and leisure and consumerist culture go more or less hand in hand. The park covers about 120 acres of land for public use, is within 10 miles of downtown Providence, and has been popular since it opened in the mid-1800s. The text between the history of Rocky Point on the Rocky Point Foundation’s page and the page for the park on Rhode Island State Parks describing the multiuse history of the site are virtually the same; both pages note that “Over the 150+ years of the property's existence, it has served as a location for nature trails, a ferry pier, an observation tower, hotels, clambakes, restaurants, a swimming pool, rides, games, and concerts.”

David Bettencourt’s documentary, You Must Be This Tall: The Story of Rocky Point, which came out in 2007 and premiered to a sold out audience, provides the background to the amusement park, with archival footage of when the park was operational to views of the park just before and during its demolition. Some famous Rhode Islanders make interview appearances in the documentary, including meteorologist Tony Petrarca, furniture sales superstars the Cardi Brothers, and former mayor of Providence Buddy Cianci, whose term in office is covered in season one of the podcast Crimetown. Other interviewees include park attendees, former park employees, and the son of previous owner Vincent Ferla. I can’t really recommend the documentary enough, because of a few things: a former park security guard describing how he threw Frank Sinatra, Jr., off his ride because he didn’t like his attitude, smoking a cigarette and drinking Dunkin Donuts inside a restaurant while he does so, ending the story with a little chuckle, so emphatically Rhode Island that when I want to describe what this place is like to people I think that’s the clip I need to send them; the archival footage of the park during its operation history and growth; the recording of its state while it rotted before being bulldozed.

I’m thinking a little bit about how painful it is when something you love dies, or how painful it is to watch a place undergo change. Do we ever feel comfortable about it? I’m reminded of a question posed in the Joshua Tree National Park Visitor Center, asking guests to think about the places we know that have changed. I think about that question often; everything changes. Part of this project is even in response to these changes. The interviewees of Bettencourt’s documentary loved Rocky Point Park. They still love it. They share their memories of the place as it was, they share memories of the place, in some cases, as it may have been even before they knew it, so deeply ingrained into us are our concepts of space. People reflect on the wild things their child eyes couldn’t believe, on the olympic sized saltwater swimming pool and the boy with no arms who would dive from the highest board and swim better than anyone else, on the open air trolleys that were exclusively run to get people from Providence to Rocky Point (and they ask—Have you ever been on an open air trolley? There’s nothing like it—), on the massive shoreside diner and the busboys who would clear the long tables and then unroll long plains of new white paper to set down to be messed again, on the fear of going through the House of Horrors and needing the lights turned on, and thinking that must have been the best ride through because they got to actually see everything in the old dark ride. Archival footage shows the park being mauled by hurricane winds and waves pulling apart buildings and boardwalks, like the future bulldozers would eventually pull it apart again in the 2000s; we want the things from our childhoods to stay permanent forever because we ultimately know that they are not. When the storm comes, it reminds us that coastlines shift, just so much. It reminds us that we can’t keep things in stasis. When we do, they fall apart. Rather than remaining what we knew it as, the memory decays. The only way to keep things is to actively do so.

The history of Rocky Point follows a similar story to the history of recreation and leisure over U.S. history; it is unique in that it is a uniquely Rhode Island place, but it is not unique in the way its various uses have changed. Leisure begins to become a regular part of American culture in the 1850s alongside industrialization, and as lands are purchased and turned into parks, some of those park owners start to think of new ways to get people to visit the parks—hence the creation of the amusement park. Defunctland, a Youtube series which documents the histories of different defunct theme and amusement parks and rides, has a few different episodes which chart these developments of park and picnic spaces into eventual amusement parks with dark rides, rollercoasters, Ferris Wheels, and the like, as well as the eventual fall of these places in the face of financial instability and loss—much of which came about in the 1990s. What happens to these places is not always a happy story. A lot of people feel grief at the loss of the amusement parks from their childhoods—but, when the rides don’t fall into disrepair, they often are purchased by other amusement and theme parks, and when communities invest in and become outspoken about the way the land ought to be used now that the park is no longer operating, these spaces can become reclaimed and turned back into places that the public can again enjoy.

In its new life as a state park, Rocky Point has somewhat returned to what had been appealing about the site in the first place. Access to the water, the ability to enjoy the seabreeze or watch the sunset over the horizon, the ability to walk through woods or along the waterfront, to be able to be outside—this all matters and provides space for people to be outdoors.

I think I need to talk about access to recreation for a second. The primary draw of local parks is that they don’t require you to have much more than the ability to get there in order to be able to enjoy many of them. Access to the outdoors matters, especially when most Americans spend less than 8 percent of their lives inside, and when we might have the perception that being outside is an inherently risky place to be. What makes getting outside so difficult? It depends. If you live somewhere that is unsafe (for whatever reason it might be), being outside puts you in danger. You can’t exercise the same artificial level of control over your environment outside as you can inside. And, depending on your job, you might not have the option to go outside at all for the entire workday. Depending on your work hours, going outside at all might not even be an option. I know that here in New England, winter can be a really difficult time for outdoor recreation; the sun comes up late and goes down early, it’s cold, and, if you’re like me and live for warm weather, your temperament might just prefer to stay inside. In an article for Outside, Maura Fox reports that likely culprits for the intensification of Americans staying inside are work, technology, and the cost of entry. It is hard to play outside if you can’t afford it. People who live in cities or in places with poor public transportation are less likely to be able to get there to be able to enjoy outdoor recreation. If you’re listening to this podcast or reading the essay, I’m probably preaching to the choir here, but in the event that you remain unconvinced that people ought to be able to spend more time outside, here’s a brief list of the benefits of being outdoors, cultivated from a few different listicles around the web:

Improved physical health, including cardiovascular health, respiratory health, eye health, and general physical fitness

Protection against some of the effects of seasonal affective disorder, improved stress recovery time, and reduction in general anxiety

Community wellness by greater investment in care for shared outdoor spaces

Improved sleep

If only a small portion of our population is able to regularly access the outdoors or engage in outdoor recreation, we’re creating larger health inequities and we’re also amplifying systems which work against better community spaces for everyone. We need to make outdoor recreation available to everyone, and we also need to take care of those outdoor spaces which are for everyone—which means, in some cases, not littering, because it’s not good stewardship, but also being vocal advocates for our parks and recreation departments, being vocal advocates about how space gets allocated and used for the public, and to make sure that we ourselves are going out and using those spaces responsibly. We ought to be doing a better job of making it possible for everyone to get outside, and if we are people who have the means to be outside, we should be taking full advantage of being out there. It’s good for us to be a part of the world that we live in. While the prospect of outdoor recreation might be a little intimidating at first, I want to offer some words of reassurance. There are accessible parks in the world, and while parts of the outdoors are by nature difficult to reach, it’s not all beyond what you can do. What is particularly good about Rhode Island’s state parks is that, for the most part, they’re free, and in many cases, you don’t need any special gear (unless it’s cold out, in which case, dress for the weather) in order to enjoy them. You can even just choose to sit on the grass or on the beach or on a bench and enjoy how it feels when the sun hits your face or the wind blows your hair. At the end of the day, you—yes, you, specifically—belong outdoors.

Theories of Rhode Island

I’ve been asked, since moving to Rhode Island from Massachusetts, a lot about the difference between the two states (if there is one at all, which most people from here would say that there is). This is a hard question for me to answer. I’ve lived in Rhode Island for five years now, and it still doesn’t really feel like home—though I grew up as close to midway between Providence and Boston as a person can really be, my own identity has always been filtered through the perception I have had of myself as a Masshole. But let’s say I’m trying to reinterpret this for myself, and to rethink of my identity as a little bit more encompassing of the larger bioregion that I’m a part of; right now, it’s easier to say that I’m a Southeastern New Englander. That was my Girl Scout affiliation when I was younger, anyway. So, in living in Rhode Island, I’ve been trying to figure out how to answer that question: what’s even the difference, anyway?

Rocky Point can be seen as emblematic of a sort of Rhode Island ethos itself. What I think I mean by this is that it’s one of those places (among many) deeply beloved by lifelong Rhode Islanders, many of whom hold nostalgia for a way of life that really doesn’t exist in the state anymore, and is exemplified by derelict structures, bankrupt community business staples, and a profound neglect of structures and spaces. There are a number of other iconic things like this in Rhode Island, that are still standing despite the genuine hazards those structures might pose, but which are landmarks for the residents of the state, and therefore, it seems, allowed to rot without intervention: other examples include the Milk Can on Route 146 in North Smithfield; the raised Crook Point Bridge between Fox Point and East Providence; the Apex building in Pawtucket—all things that have been kind of stuck in their place or tied up because of outside factors, such as pollution, changes in transportation technology and the development of interstate highways, or the fairly straightforward lack of money to deal with them, and their permanence as memorials to an older version of Rhode Island, or what Rhode Island was to longtime residents of the state and the value that this vision of the past has to the people who still live here creates stasis. The structures are often only taken down if people have been actively harmed by their rot, such as when several teenagers were injured when playing around The Bells at Brenton Point State Park. These structures are falling apart. They would be considered eyesores if they had the misfortune to belong anywhere but Rhode Island. They are often neglected (though someone takes care to paint over graffiti on the Milk Can). They are visibly deteriorating, rusting, losing panels—yet, they stand. The cost to demolish any of them might be too high from both a monetary and a cultural point of view, but it’s not like anyone’s shelling out the money to restore these places, either, and love for a place can’t keep it together if you don’t have the cash to maintain it—and that might be a recurring theme for this project, since the role of cash in the upkeep and ownership over these places plays a significant role in who ends up holding stewardship over them.

Rhode Island is a state which thrives on its popular culture: I think about the love for its lowbrow iconography, such as for Nibbles Woodaway, the Big Blue Bug visible on I-95, or for Olneyville NY System, a staple of post-drinking, late night feeding—or Rocky Point. Rhode Island is, in many ways, a state with a very townie, maybe blue collar type of culture, which might also seem contradictory if all you know about the place is that it’s the home of Brown University and the Newport Mansions.

This version of a quirky, weird, small-town state—which is how I think many lifelong Rhode Islanders think of it—is in direct competition, it seems, with the kinds of economic development plans taking place in the state, most obviously in the city of Providence. One really only has to look at the new structures being raised in Downtown to see a conflict of architectural ethos and aesthetic, with new builds looking a lot like they came out of a box of Legos. Many old storefronts, dating back to the department store boom of the turn of the previous century, had been turned into restaurant spaces—restaurant spaces which are now largely empty. The contemporary buildings lack in the same individual character and, dare I say it, charm that the rest of Rhode Island generally has, as though newness needs to mean conformity, neglecting, of course, that at one point, all of the buildings in Downtown Providence were new, and that all of the buildings bear the mark of their era—by trying to build things that look as though they belong to some future, the design inherently showcases the laziest version of 2020 aesthetic. You can almost forgive the refusal to give up the past when the future looks so bleak and boring.

Outro

So, should you visit Rocky Point State Park? Yes. It is an easy park, and if you’re someone who is new to outdoor recreating, or just looking for something that will get you outside but won’t require anything special of you, there are plenty of easy trails to walk and space to run. You can even bring your dog, if you have one. The views are representative of one version of Rhode Island, a version of Rhode Island that reminds you how close you are to the water at all times, a version which has a long history and the continual love of devotees to the place. It might not feel all that “out of this world,” as some natural places are, though in the spring and summer, its flora are striking, even though some of it might be invasive. It would probably be worthwhile for the state government to give RI Parks more funding to have park personnel there if only to be able to keep the place clean, or to remind others to do so—but this, I’m finding, is a continual problem in many of the state parks, and outside in general. We need to do a better job of reminding ourselves and others of the principles of Leave No Trace, and maybe that looks like better signage, better community building, and developing a stronger respect for the environment as a culture in Southeastern New England, where the density of people means that the litter builds up quick. Rocky Point State Park is only a park and not a housing development because the people who live there and love that space worked together and spoke up to protect it—so if there are places you care about, it is really up to you and your community to save them and preserve them—not just for yourself, but for your children, and for your children’s children.

References

“America at Leisure | Articles and Essays | America at Work, America at Leisure: Motion Pictures from 1894-1915 | Digital Collections.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/america-at-work-and-leisure-1894-to-1915/articles-and-essays/america-at-leisure/. Accessed 11 January 2025.

B, Nicola. “Rocky Point Amusement Park.” Atlas Obscura, 17 January 2022, https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/rocky-point-amusement-park. Accessed 4 January 2025.

Bettencourt, David, director. You Must Be This Tall: The Story of Rocky Point. 2007. YouTube,

Accessed 9 January 2025.

Borkowski, Rob. “Warwick, State Officials Celebrate Rocky Point Park’s Debut.” Warwick Post [Warwick, RI], 24 October 2014, https://warwickpost.com/warwick-state-officials-celebrate-rocky-point-parks-public-debut/. Accessed 5 January 2025.

Buchholz, Katharina. “Infographic: Americans Spend Less Than 8 Percent of Their Time Outdoors.” Statista, 16 April 2020, https://www.statista.com/chart/21408/time-americans-spend-indoors-outdoors/. Accessed 4 January 2025.

Dunning, Savana. “The Bells is gone from Brenton Point State Park. What's next for the site.” The Newport Daily News [Newport, RI], 27 February 2024, https://www.newportri.com/story/news/local/2024/02/27/the-bells-at-brenton-point-state-park-newport-ri-demolished/72751234007/. Accessed 5 January 2025.

Fox, Maura. “Americans Are Spending Less Time Outside.” Outside, Outside Interactive, Inc., 30 January 2020, https://www.outsideonline.com/health/wellness/americans-less-time-outside-2019-study/. Accessed 4 January 2025.

Goldstein, Alan P. “Milk Can.” Art in Ruins, https://artinruins.com/property/milk-can/. Accessed 5 January 2025.

Merrick, Janie. “Rocky Point Park is Not Forgotten.” Rhode Tour, https://rhodetour.org/items/show/331. Accessed 4 January 2025.

Rocky Point Foundation. “Rocky Point Park: A Cultural Heritage.” Rocky Point Foundation, https://rockypointfoundation.org/saga. Accessed 4 January 2025.

“Rocky Point State Park | Rhode Island State Parks.” Rhode Island State Parks, https://riparks.ri.gov/parks/rocky-point-state-park. Accessed 4 January 2025.

Tripadvisor. “Rocky Point State Park.” Tripadvisor, https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g54121-d7385943-Reviews-Rocky_Point_State_Park-Warwick_Rhode_Island.html. Accessed 4 January 2025.

Share this post